The Academic Period

In the early Nineties, community design moved from its pragmatic period into its academic period. From the soft privatization of America’s public housing through HOPE VI to universities becoming more involved in community design and research, development began to shift from being largely housing oriented in the Eighties to becoming more commercially oriented.

1990

The Restructuring of Power in NYC via Charter Revision

Throughout the course of this history in New York City, the municipal governance structure rested heavily on the centralized power of the Board of Estimate: a government body responsible for policies like the city’s budget, contracts, water rates, land use, and zoning. In 1989, the United States Supreme Court declared the Board of Estimate as unconstitutional on the grounds that the city’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, had no greater representation than the least populated, Staten Island. This constituted a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Board of Estimate was abolished by a citywide referendum in November 1989, and a new system of municipal governance was implemented in 1990. The board’s powers were transferred to an expanded City Council, and the urban dynamics of the city changed overnight. A new position of Public Advocate was established, a City Planning Commission was created to oversee land use, and term limits on elected officials were enacted. The goal was to further democratize the local political environment.

Image: New York City Municipal Library

The most significant outcome of the effort to democratize the process was the empowerment of community boards, which had been created in 1975. With members appointed from the public by the Borough President and City Councilperson, the community board was an advisory body meant to assist with the city’s new land use processes and communicate constituent concerns on neighborhood matters.1

1991

US launches operation Desert Storm with a coalition of 35 nations to liberate Kuwait from Iraqi forces

1992

HOPE VI-ing of American Cities

Image: Lawrence J. Vale via Places

Starting in 1989, a three-year investigation by a Congressional commission discovered that 86,000 units across the country -six percent of housing stock- qualified as severely distressed. As a response, Congress created a program called HOPE VI in 1992 to rehabilitate those public housing units. The official mission of HOPE VI, administered through Housing and Urban Development (HUD), was to revitalize the most dilapidated public housing stock. But the renovations were done according to principles of New Urbanism resulting in low-density, defensive architecture.

The intention was to mitigate crime by producing low density developments and re-integrating them into neighborhoods. This facilitated displacement and gentrification through increased local property values. Concurrently, the number of new units constructed never reached the amounts that were demolished, and most of the program’s funding went into Section 8 vouchers. The redevelopments further exacerbated pre-existing crises facing communities of color.2

1993

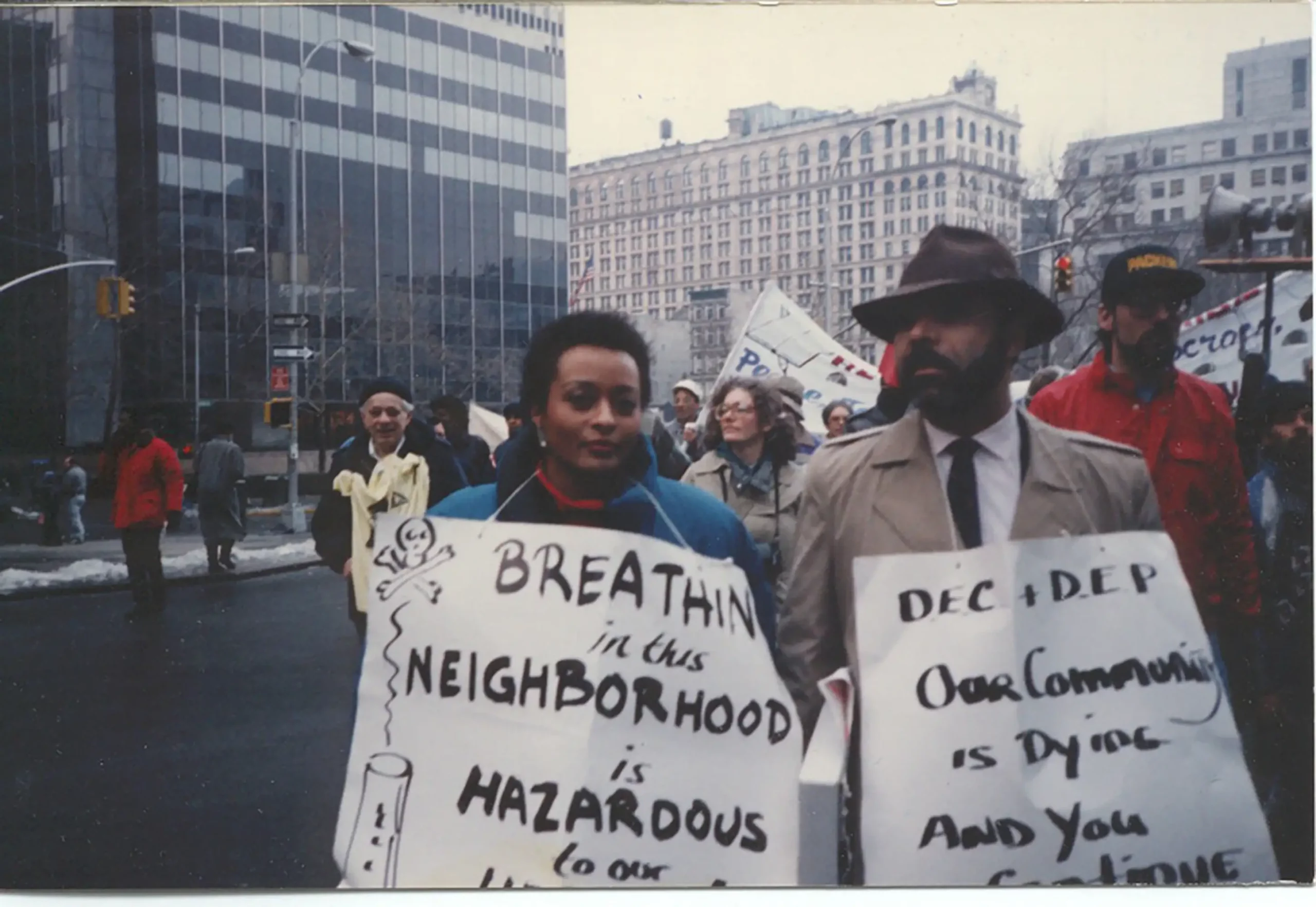

Environmental Justice & Inequities in the Built Environment

After the tumult of the 1970s and 1980s, many of the city’s communities with large populations of people of color encountered trouble in preservation and development due to the presence of ‘locally unwanted land uses’ (LULUs): uses that create hazards and reduce home values for those who live in close proximity to them. The progress made with the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) did not expand to waterfront industrial neighborhoods, and the city did not commit to any form of land use policy to encourage changes that might reverse the concentration of LULUs. Instead, the city focused on upzoning already well-off neighborhoods to bolster the real estate industry and improve its tax base.

According to Tom Angotti, founder of the Hunter College Center for Community Planning and Development, there was a dilemma in responding to LULUs: allowing them to exist further caused health problems for an already precariously located community, but removing them would accelerate gentrification that the LULUs kept at bay. Organizers came to see community planning as the tool to address both threats of LULUs and displacement.

Image: West Harlem Environmental Action

Activists Vernice Miller, Peggy Shepard, and Chuck Sutton organized West Harlem Environmental Action (WE ACT) in 1988 to challenge the city’s continued ignorance of disparate health effects in communities after the construction of a sewage treatment facility in West Harlem. Even though the city constructed a new greenspace, the odors generated by the facility made locals wonder if it was one of the factors causing Harlem to have one of the highest asthma rates in the country. Activists took the city to court and won a million-dollar settlement to create a fund to address the community’s concerns. The court ordered the city to fix the plant and installed WE ACT as the official monitor. They created a community plan for the Harlem waterfront and are still active today using activism and planning to address major projects in the area, like Columbia University’s West Harlem Expansion Plan.

Image: Luis Gonzalez via UPROSE

At the same time in Brooklyn, the city announced plans to move sludge plants from Red Hook to Sunset Park, a working-class neighborhood of Latino, Asian American, and Italian American communities. Leading the United Puerto Rican Organization of Sunset Park (UPROSE), Elizabeth Yeampierre brought the community together in its opposition to the plant by calling out environmental injustice. The city pulled the plan in 1993 and UPROSE continued to be a major voice for community planning and empowerment.3

1994

Universities as Incubators of Local Design

The federal government re-entered community design in 1994 by founding a new program, Community Outreach Partnership Center (COPC). Administered by Housing and Urban Development, the COPC’s objective was to foster collaboration between local government, academic institutions, and communities. Through a competitive grant, this program used its funding to encourage collaboration between academic institutions and local community groups to strengthen the capacity of the neighborhood and improve the community’s physical, environmental, and economic conditions. Some of the examples of this collaboration included (1) job training and counseling to reduce unemployment, (2) resident-backed strategies to spur economic growth and reduce crime, (3) local initiatives to combat housing discrimination and homelessness, (4) mentoring programs for neighborhood youth, and (5) financial and technical assistance for new businesses. Some of the successful examples that came out of the program include the Oakland University’s Oakland Enhanced Enterprise Community Program and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro’s Center for the Study of Social Issues.4 5 6

Image: Rural Studio

Furthermore, community design centers embedded in universities increasingly started becoming recognized as incubators of design, innovation, and experimentation in planning and architecture. Building the spirit of professional outreach into local communities, professors and students collaborated with local communities to develop sustainable and context-sensitive solutions, reshaping the way architecture reached local communities. Rural Studio became one of the most celebrated early adopters of this type of academic design center by marrying a community oriented mission with high quality design and construction.

1997

Comprehensive Community Initiatives

Image: The Brookings Institution Press

At a national level, the housing-centric approach of community development began shifting to more holistic development strategies that encompassed economic, social, and environmental dimensions. The focus was now on creating and fostering vibrant, equitable, and sustainable communities.

In the early 1990s, local activist groups from Detroit, Memphis, and Milwaukee secured a decade-long investment from the Ford Foundation’s Neighborhood and Family Initiative (NFI) to improve the conditions of their local neighborhoods. The NFI was an example of a Comprehensive Community Initiative (CCI), also known as place-based initiative, launched by charitable and philanthropic organizations in the 1990s and 2000s. While methods and goals varied by location and organization, they all tried to bring in investment and lessons from the past to help enact broad-based changes at the neighborhood level.7

1998

President Bill Clinton is Impeached by the House of Representatives on the grounds of perjury and obstruction of justice

CCIs emerged in response to broader national questions on the validity of America’s welfare programs in the mid-1990s. These initiatives coordinated efforts across multiple sectors to address complex urban problems. CCIs were meant to empower communities by integrating social, economic, and environmental interventions, and promoting holistic development that benefited all residents.8 However, this type of action failed to move beyond meeting short-term, shovel-ready goals like housing construction or infrastructure rehabilitation. As Brett Theodos of the Urban Institute remarked at the time, putting millions of dollars into a small area, and calling it an initiative, is not enough to ensure that progress and success metrics will be met. Theodos emphasized the need for charitable organizations to make twenty- or thirty-year commitments to achieve long term success.9

Footnotes

- Amy Widman, Replacing Politics with Democracy: A Proposal for Community Planning in New York City… (2002) ↩︎

- Lawrence J. Vale, From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors (2007) ↩︎

- Tom Angotti, New York For Sale: Community Planning Confronts Global Capital (2011) ↩︎

- Avis Vidal, Nancy Nye, et al., Lessons from the Community Outreach Partnership Center Program (2002) ↩︎

- Marcia Marker Feld, Community Outreach Partnership Centers: Forging New Relationships between University and Community (1998) ↩︎

- Margaret Bourdeaux Arbuckle and Ruth Hoogland DeHoog, Connecting a University to a Distant Neighborhood: Three Stages of Learning and Adaptation (2004) ↩︎

- Karen Mossberger, From Gray Areas to New Communities: Lessons and Issues from Comprehensive U.S. Neighborhood Initiatives (2009) ↩︎

- Matthew W. Stagner and M. Angela Duran, Comprehensive Community Initiatives: Principles, Practice, and Lessons Learned (1997) ↩︎

- Meir Rinde, Did the Comprehensive Initiatives of the 1990s, early 2000s Bring About Change (2021) ↩︎